CLEOPATRA

THE TWO MILLION DOLLAR MOVIE

TIMES 200

This is where and how a simple collection of words in a library book provoked a series of images that kick-started a three-year adventure that took us around the world from Hollywood to London to Rome to Naples to Cairo and back again.

How did CLEOPATRA all begin? As I write this, I can look up to a small door sign with my father’s name on it. It originally hung on his office door in the art department at 20th Century Fox, just off Olympic Boulevard in Beverly Hills, now adjacent to Century City. Its fabrication is amusing in that some of you (older designers) will remember that there was a time when we bought wax sheets of lettering and by rubbing on the letter in question, the letter would transfer to the intended surface. That was how this sign was made. Behind this sign and behind the door it was on, a conversation took place between my father and Walter Wanger. Now, just who was Walter Wanger?

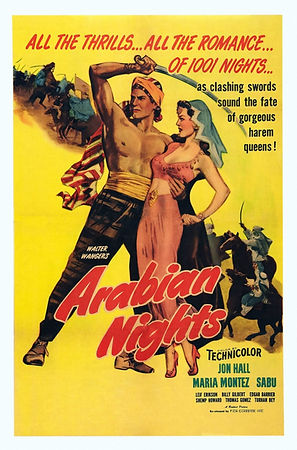

Walter was an American film producer active in filmmaking from the 1910s to the turbulent production of CLEOPATRA in 1960-63. Walter and my father first became acquainted as early as 1942 when Dad was painting matte shots for the film Arabian Nights, which Walter produced.

Wanger gained recognition as an intellectual and socially conscious movie executive who produced thought-provoking message films and lavish romantic melodramas. He was heavily influenced by European cinema and created many productions aimed at international audiences.

His career began at Paramount Pictures in the 1920s, and he eventually worked at nearly every major studio, either as a contract producer or an independent. Unfortunately, he spent four months in jail for attempted murder after shooting his wife's lover. Wanger suspected that his beautiful wife, actress Joan Bennett, was having an affair with her agent, and private detectives had seemingly confirmed his worst fears. However, Walter was not the type to be held back by a few months in prison. He later produced the film "Riot in Cell Block 11" (1954), which was inspired by his own experiences in jail.

My father first met Walter in 1942 at Universal Studios while they worked together on the romantic swashbuckler film, *Arabian Nights*. At that time, my father painted the matte shots for the film, which was notable because, for the most part, matte shots had previously been done in black and white. The transition to color challenged the matte artists to engage in color palette work.

At the time, I was an architectural student at USC, apprenticing while also working in my father's office at Fox. It was during this time that Walter came in, placed a library book on the desk, and asked my father to design the film *Cleopatra*.

Two unique coincidences converged, leading to the Cleopatra affair. First, Fox was searching through their archives to find a modest budget film that they owned the rights to, and they came across the property titled CLEOPATRA. At the same time, producer Walter Wanger had been working on the concept of making CLEOPATRA. When these two needs aligned, as David Brown famously put it, they decided to persuade Walter to produce the film.

Dad loved the idea and, as any self-respecting designer would, asked to read the script. However, Walter grabbed the library book and mentioned that the script was still in progress. In the meantime, he had marked ten passages in the library book titled "The Life of Cleopatra."

“Now, John,” he said, “I want you to begin illustrating the passages I’ve marked. Don’t worry about the script; that will come later.”

If only one could have glimpsed five years into the future, they would have seen Joseph Leo Mankiewicz, the director, being carried on a stretcher through the sands of Egypt, writing new pages for that day's shoot.

My father went to work, and several weeks later, the phone rang. It was Walter, telling John to gather his renderings and meet him at Zanuck’s office, the head of 20th Century Fox. According to the story, they met in the elevator, where Walter said to John, “I’m going to give my pitch. When I pause to catch my breath or stop for a drink of water, you can jump in and start talking about the art and beauty of Cleopatra’s world. As soon as I’ve caught my breath, you sit down, be quiet, and let me take over.”

The presentation went well until Zanuck asked the $64 question. “Okay, Walter, I like it. What’s it going to cost?” Walter replied, “Two million. We can make this movie for two million dollars.” Zanuck, a seasoned professional, looked up at Walter, peering over his reading glasses with a quizzical expression. “Two million, Walter?” Walter assured him, “Absolutely, Daryl, not a penny more.” Zanuck responded, “Okay, let’s move forward… but not a penny more.”

Walter and my father left the office and walked down the hall to the nearest bathroom to relieve themselves. Standing side by side, John said to Walter, “We can never make this film for two million dollars.” Walter replied, “Oh, John, my son, relax; that’s just the first two million.”

Adjusted for inflation, “Cleopatra” ranks as one of the most expensive films ever made. Originally, the movie had a modest budget of $2 million, but it ultimately ballooned to an estimated $44 million, which is equivalent to about $466 million in 2025 dollars. Despite being widely considered one of the biggest box office failures of all time, it was, in fact, the highest-grossing film of the 1960s. The film eventually recouped its costs, partly through worldwide box office sales and by selling two television spots for the film to ABC-TV for $5 million in 1966. After breaking even in 1973, the studio kept future profits secret to avoid paying those who might have been entitled to a percentage of the net profits.

In summary, fast-forwarding 30 years, we found a collection of original sketches that my father had created for Walter. Unfortunately, these sketches had been photographed on Kodak “Professional” Ektachrome film, which is known to lose its colors and take on an unpleasant magenta hue over time. Thankfully, thanks to the dedicated efforts of the Media Center at the University of Asbury in Kentucky, we were able to restore these positive transparencies to their original brilliance. I have included a few for your enjoyment.